Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura and the Baptist Poetess

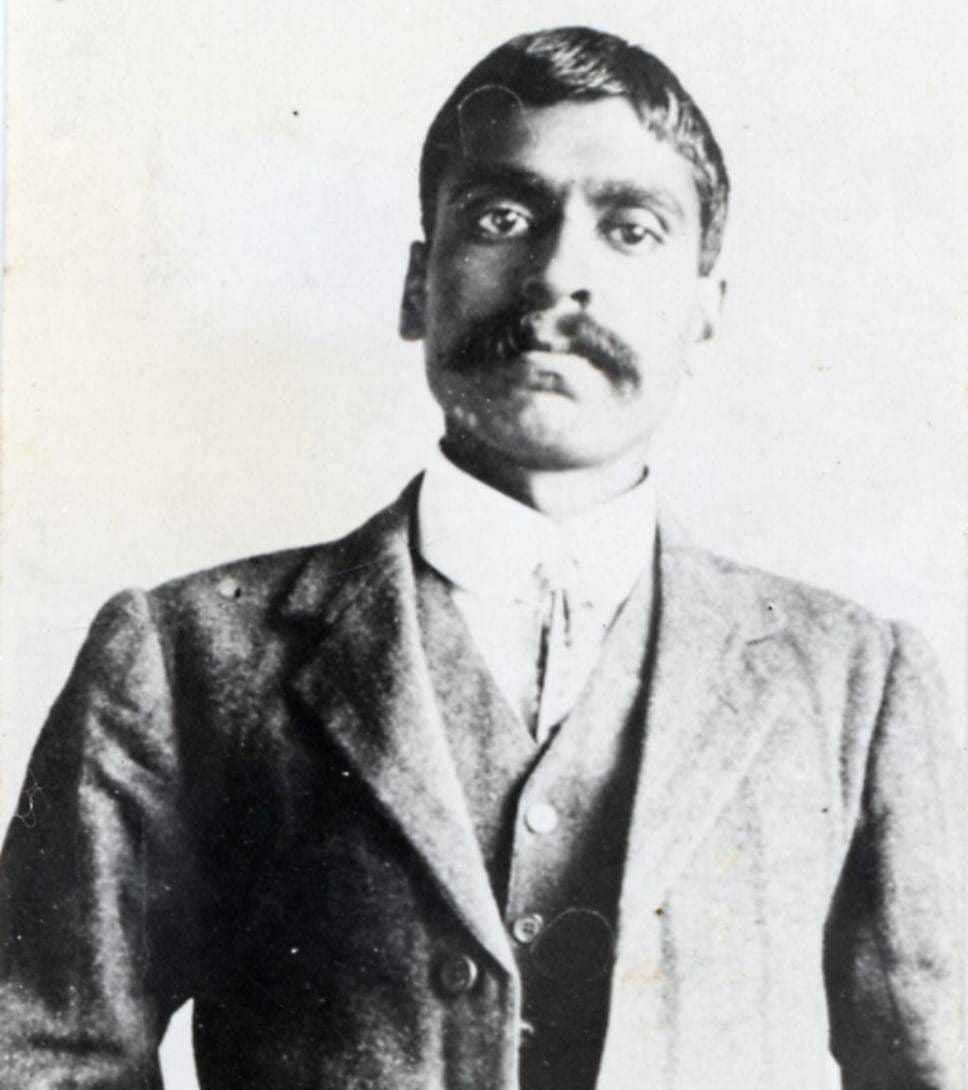

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura—poet, schoolteacher, novelist, magistrate, philosopher, father to ten children, spiritual reformer, mystic, Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava prophet, and more—was born Kedarnath Dutt into a wealthy, prestigious Bengali family of Ula, Birnagar. His grandfather possessed a grand estate that is still a heritage site in the Nadia district. During the Ṭhākura’s early childhood, when his family was at the peak of its prosperity, they had hundreds of male and female servants, hosted elaborate religious festivals, and effectively maintained a sizable idyllic village of largely carefree people who excelled in music and fine arts. This utopia was short-lived, however. In 1856, an epidemic of cholera decimated the village.

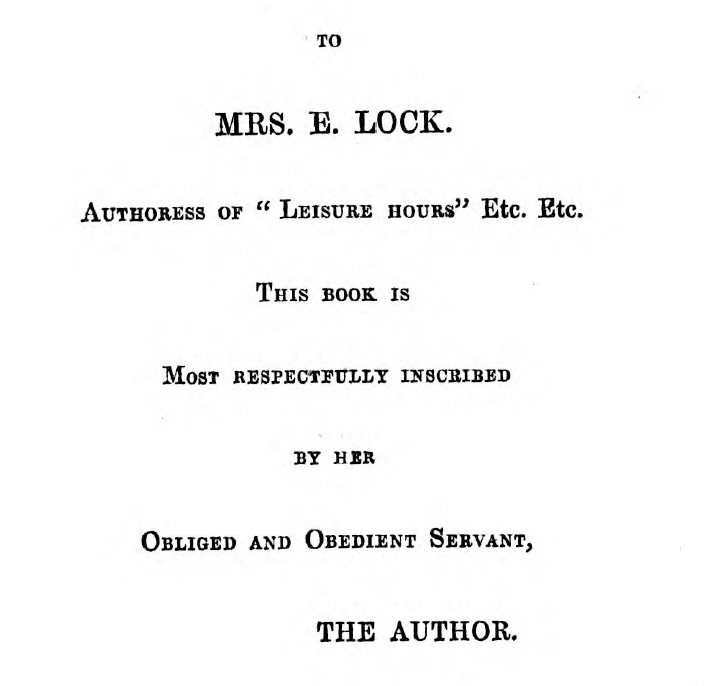

The Ṭhākura was one of the few survivors of this tragedy. Overcoming various challenging twists of fate and aided fortuitously by some distinguished relatives and friends, the Ṭhākura eventually flourished in Calcutta among the intelligentsia of his day by dint of his literary strengths and interests. An astute, thoughtful young man secretly battling loss and bouts of depression, he mingled with famed poets, esteemed professors, holy reverends and missionaries, and various members of the illustrious Tagore family. Among his assorted acquaintances was a spiritually eccentric American Baptist woman who was twice his age: Mrs. Lydia Lillybridge Simons, or Mrs. E. Lock, as the Ṭhākura refers to her on the dedication page of The Poriade, his 1857 debut volume of English poetry.

Despite the age difference, and the cultural one, the Ṭhākura and Mrs. Lock seem to have shared a close friendship over the course of perhaps two or three years, some of which were the most challenging of the young Ṭhākura’s life. While the dedication page of The Poriade is one clue and some indications are provided in the Ṭhākura’s few references to her in his autobiography, perhaps the best and hitherto untapped resource to understanding this most unexpected of friendships is Mrs. Lock’s own solitary work, known in short as Leisure Hours, which had been published a decade prior to their acquaintance.

The following essay attempts three goals: (1) to capture as briefly as possible the story of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s development as a writer of English poetry as disclosed in his autobiography; (2) to make sense of The Poriade itself, which stands out among the Ṭhākura’s numerous works not only as his first official publication in English but also as a somewhat puzzling work for Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas due to its ostensible lack of bhakti-centric content; and (3) to bring into focus the distinctly sāragrāhī (essence-seeking) nature of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s character and pastimes by highlighting what appears to be a unique interfaith co-pollination involving not only Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura and Mrs. Lock, but also the Ṭhākura’s famous poet uncle, Kashiprasad Ghosh.

Early Appreciation for the Mahābhārata

At the age of seven, Kedarnath Dutt, later Ṭhākura Bhaktivinoda, moved from his family home in Ula to nearby Krishnanagar along with his elder brother, cousin, and other peers. There they began attending a boarding school of sorts at the behest of the Krishnanagar king, Shrish Chandra. Kedarnath, the youngest of the bunch, was so anxious about the arrangement that his mother had to send his personal nursemaid with him at first.

The boys were accommodated in a two-storey house located in the town bazaar. Their rooms consisted of an upstairs sleeping quarter and a downstairs kitchen. Next to the kitchen was a dry storage for the oil press next door. The seeds would fall through the cracks in the door, recalls the Ṭhākura, and the boys would collect them, fry them, and eat them.

The Ṭhākura mentions there was a statue of Gaṇeśa, Vyāsa’s elephantine scribe, above the stairs. He remembers that, sitting on the stairs, he was able to see into the workshop of the very elderly man who operated the oil press while sitting on a low seat. The elderly man, in pious anticipation of his impending death, had arranged to have the ancient epic of Mahābhārata read aloud in his courtyard. The speaker sat on a raised seat beneath a decorative canopy and did his recitation, likely from a poetic Bengali adaptation, as the Ṭhākura recalls him breaking into song from time to time.

Listening to these recitations as he sat on the stairs beneath the sacred image of Gaṇeśa, the scribe of the Mahābhārata, appears to have been the highlight of this period for young Kedarnath. He mentions that he found himself most captivated by the stories about the powerful Bhīma, known for his tremendous strength, insatiable appetite, and fierce temper.

“Mr. ABC”

It was in Krishnanagar that Kedarnath began studying English, and he excelled, gaining favor among the teachers and prestige in the class. He was promoted to a higher class and received an award. None of the other boys he studied with experienced such success. When they returned to Ula on the weekends, his relatives showered him with praise and affection.

The abundance of praise backfired, however, deflating Kedarnath’s enthusiasm. His performance suffered and his classmates, who had been jealous, took the opportunity to berate him. Their jealousy surfaced in full force, torment closed in on him from all sides, and he found himself unable to memorize his lessons any longer.

Kedarnath began skipping school, leaving the house on the palaquin that carried the boys to school but then hiding in the woods till classes were over. Some days, he stayed home entirely, feigning illness. Kedarnath’s nursemaid had returned to their hometown and the one remaining household servant sympathized with him, indulging the behavior.

Some time later, Kedarnath’s elder brother suddenly came down with cholera. The boys swiftly returned to their hometown of Ula by palaquin, but shortly after arriving, the elder brother died. After that, Kedarnath’s parents did not want to send him back to Krishnanagar, and his own disinterest in studies was welcome news to them. This lasted three or four months, during which Kedarnath forgot all the English he had learnt. But an English school was soon set up in the village and he resumed his studies, excelling once again. Meanwhile, he also studied math and Bengali in front of the charming family deity of Krishna Chandra Ray.

All was well in the idyllic village of Ula for a time, but the Ṭhākura recalls a sudden turning point when a maternal uncle of his died. Everything started to go wrong for the family. The Ṭhākura’s grandfather, the patriarch of the family, succumbed to swindlers and fell into debt. One by one, the Ṭhākura’s four brothers died, leaving just him and his infant sister. By the time the Kedarnath was eleven, his father had died too, after many desperate efforts to secure his son’s future.

Without his father, the Ṭhākura recalls feeling lost and alone, as if engulfed in darkness. He felt he was floundering at school, progressing very little with no one to take a serious interest in his development. He did reasonably well in literature but struggled with math. His teacher showed him kindness, but a cloud of depression hovered over him. He began to consume castor oil secretly to make himself sick. Still, he managed to stay out of trouble and turned to poetry, channeling his troubled spirit into a glorification of the local village goddess, Ulā Caṇḍī, written in Bengali.

In an attempt to salvage her son’s future, Kedarnath’s mother arranged his marriage. He was twelve and his bride was five. He describes the marriage as that of dolls. He was even too nervous to stay in his father-in-law’s home on the wedding night, so his nanny had to accompany him. As was customary, he and his bride lived apart till she was of mature age.

It seems that it was at his in-law’s home in the nearby village of Khishma that the Ṭhākura first encountered Englishmen, military personnel, and struck up conversations with them. He recalls being very curious of the finely dressed English women, and when missionaries came to town, he was sure to go to see them.

He had always had a keen interest in God. He persistently inquired of the various people in his life—maids, guards, carpenters, etc.,—regarding God. It seems he eventually came away with some faith in the name of Lord Rama and belief in one supreme God.

When Kedarnath was about fourteen, one of his maternal uncles, Kashiprasad Ghosh, who had gained considerable fame as the first Indian to publish a volume of English poetry, came to Ula for a family visit. One day, he tested Kedarnath’s skills in reading and writing. Impressed with the young Ṭhākura, Kashiprasad had his wife, Kedarnath’s aunt, convince her sister to let her only remaining son go to study in Calcutta, where he had a shot at a proper education.

Once Kedarnath’s mother overcame her reluctance, Kedarnath moved to Calcutta, where he initially lived with Kashiprasad Ghosh in a nice neighborhood surrounded by various schools and the homes of missionaries. With the help of his aunt and uncle, Kedarnath flourished. Through Ghosh, Kedarnath was exposed to the intelligentsia of Calcutta—writers, artists, poets, professors, priests, activists.

One by one, Kedarnath read all the books in Ghosh’s library, including many English books on philosophy. By his third year in Calcutta, Kedarnath began writing for the Hindu Intelligencer, an English journal Ghosh edited, and delivering occasional lectures in English. Though he still fared poorly in mathematics, his literary competence earned him the respect of his classmates and teachers, and he began to write poetry that impressed them all and even drew the attention of the principal of his school.

By the end of the school year in 1854, Kedarnath was determined to proceed to university, but upon arriving at the town hall for the entrance exams, he came down with a fever. Deprived of higher education for a time, he turned to other avenues, venturing daily to Metcalfe Hall, which housed the Calcutta Public Library, and reading voraciously. He frequented various debate clubs and associations, where he met various distinguished gentlemen. One Reverend Dal instructed the Ṭhākura in the art of philosophical discussion. The Ṭhākura writes that George Thompson, the British parlimentarian and abolitionist, taught him tricks to master public speaking such as standing in a field and practicing one’s speech while imagining the assorted plants to be the audience.

By the end of 1856, young Kedarnath, who was just eighteen, had composed the first part of The Poriade. He read all of Milton with the help of another reverend and regularly accompanied an acquaintance from Ula to the home of one Grub Saheb to read Edison. He read Carlisle, Haslett, Jeffrey, Macauley, and others. He composed short poems that were printed in the Calcutta Library Gazette, and he became known as “Mr. ABC.”

Mrs. Lock

One day, he was invited to visit one Mrs. E. Lock, which appears to be a maiden name, through their mutual acquaintance Reverend Dal. Mrs. Lock looked over young Kedarnath’s poetry and chatted with him at length. She was very pleased with his compositions and praised them. Mrs. Lock must have made an impression on the Ṭhākura, and her earlier published works may reveal why, for Ṭhākura later dedicated the book to her as follows:

Mrs. Lock, or Mrs. Lydia Lillybridge Simons (1817–1898) was an American woman in her late thirties. She was a faithful Baptist Christian and published poet. Her primary work, Leisure Hours: or, Desultory Pieces in Prose and Verse, is a collection of writings published in 1846 and is attributed simply by the initials “E. L.”

After living in Calcutta for several years and publishing her collection of prose and verse, in July of 1846, she had sailed to Burma as Miss Lydia Lillybridge, where she laboured diligently in service to the Morton Lane Girls’ School in Moulmein (Mawlamyine), which had a boarding department for Eurasian girls. She was closely associated with Mr. Adoniram Judson, a prominent American Baptist missionary in Burma, and his wife, Mrs. Emily Judson, an American writer.

Eventually, on May 13, 1851, Miss Lydia Lillybridge married one Reverend Thomas Simons, a missionary who had been in Burma since 1833. He had been married once before and had four children. His previous wife, Caroline Jenks Harrington, had died in 1843. Two years later, he had relocated their four children back to America and arranged for their education there. Then he had returned to Burma in 1847 to continue his religious labours.

Miss Lillybridge also appears to have been married once before, as her 1846 work includes a poem entitled “My Husband’s Tomb” (page 141). She and the Reverend Simons proceeded to have two children of their own. As of 1890, only one of their children is said to have survived. It is possible that one of the children died early on. Perhaps this or some other difficulty prompted a separation between the couple. Records show that in 1854, Reverend Simons removed himself to Prome, on the Irrawaddy, where he performed his missionary work for the next twenty-two years of his life before dying of cholera in 1876.

While the American Baptist Missionary Union records Mrs. Lock, or Simons, as accompanying Reverend Simons in Prome until 1874, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s autobiography indicates she returned to Calcutta at least briefly and was going by her maiden name. Whatever the reason for her return, her book of poetry suggests Calcutta was a favorite spot of hers. It was here, a decade prior, that she had composed a fair amount of stirring poetry on a vast range of subjects ranging from the Divine Couple Radha and Krishna in Vrindavan—though she was clearly a devout Christian—to meditations on Creation, Jesus, trust in God, loss, the Greco-Turkish conflicts, or even things as simple as a dew drop on a leaf:

I love to view the dew-drop trembling

On the Jasmine leaf, resembling

The pure, the salutary tear,

That flows from penitence sincere.

I love to list the murm’ring breeze,

Stirring the foliage of the trees,

Which, as it whispers seems to say,

“I thus to God my homage pay.”

I love to sit here isolate,

And think upon an after state;

And though I am left all alone,

My Father views me from His throne.

—“Some Things That I Love” Leisure Hours, page 53

From her poetry and prose, Mrs. Simons, or Lock, comes across as a profoundly gentle and thoughtful soul firmly devoted to God, clearly egalitarian in her worldview, and possessed of a deep love for Bengal, India, and even the deeper layers of its culture and religion. Her repeated references to “Brindiabon” and Radha and Krishna make this clear.

How and why exactly she ended up back in India after her missionary work and marriage in Burma is not clear, but from the Ṭhākura’s own autobiography and the dedication page of The Poriade, she appears to have been in Calcutta around 1856–57. While Mrs. Lock’s husband, who was possibly estranged to her at the time, would later die of cholera, the young Kedarnath was about to have his fateful, lifechanging encounter with the disease at that time.

A Desolated Hometown

It seems almost everyone died of cholera is those days in that region of the world. Before attempting his university entrance examinations for presumably the second time, the Ṭhākura made a trip back to his hometown of Ula. He had not heard any news from home in some time.

When Kedarnath docked in Ula after a stormy night up the Ganges by boat, he and his companion found a group of men laughing and joking in a stupor of cannabis intoxication. Other than these madmen, the village was desolate. It had been decimated by cholera. The scene the Ṭhākura describes is gruesome: corpses lying all about, most houses deathly silent, others punctuated by wails of pain from those dying, and the local dogs in a craze of bloodlust, fearless of humans, emboldened by the abundance of human flesh.

Rushing to his home against the advice of friends and neighbors, he discovered his last sibling, his younger sister, had died and his mother was sick, though she seemed to be recovering. The next day, he quickly evacuated his mother and grandmother to Calcutta, stopping in Ranaghat briefly to check on his ten or eleven-year-old bride, who was also sick but recovering. Back in Ula, thousands died within a few months. Survivors fled en masse.

Yet this was not the first time cholera had struck the town. There had been recurrent outbreaks in the region since at least 1817. The name “Ula” itself came from the Bengali word for cholera—“olāuṭhā,” which literally means “to come up and out.” Evidently, the local goddess was named Ulā Caṇḍī in an attempt to ward off this recurrent curse.

Turning to God

Young Kedarnath entrusted the care of his elderly grandmother to a relative in Calcutta and found his mother accommodations elsewhere. They had no money and no one to help, because people thought his mother was rich. Meanwhile, Kedarnath himself battled cholera fevers three times in a row while trying to take care of his mother and grandmother and study for his entrance examinations. In his autobiography, the Ṭhākura confesses to suffering profoundly during this period till he gradually found solace in heartfelt discussions about God with some select friends.

At first, he found no one he could properly converse with. But he began visiting Dvijendranath Tagore, the older brother of his schoolmate Satyendranath. The Ṭhākura gushes in appreciation of Dvijendranath, lauding him as the closest friend he ever had. Dvijendranath was of good honest character and detached from worldly matters. In his company, the Ṭhākura turned his thoughts exclusively to the science of God—for it was the only science that quelled the anxiety cropping up in his heart, he writes. He read Kant, Goethe, Swedenborg, Schopenhauer, Hume, Voltaire, and others, and discussed them with Dvijendranath.

The young Kedarnath, finding his mental strength doubled by the words and company of Dvijendranath, became a regular guest speaker on philosophy at some academic clubs. He was then invited to the British India Society, which was an unlikely alliance between British and American abolitionists, former East India Company (EIC) officials, private merchants, and members of the Bengali elite. It had formed in 1839, just a year after the Ṭhākura’s birth. Although it was a short-lived organization, its members posited that India’s vast agricultural potential could ethically produce sugar and cotton to outcompete and eventually dismantle the slave-based economy of the American South. They simultaneously advocated for private enterprise and the reform of the East India Company’s governance.

Kedarnath Dutt, just nineteen years old, delivered a presentation at this assembly that was welcomed as profound and thought-provoking. At another meeting of this same group, he recited his own English rendition of Vetāla-pañcaviṁśati, an 11th century Sanskrit compilation of fables. That day, the Ṭhākura notes, a great debate ensued, and from then on, he was lauded a logician among his friends.

Reverend Dal, a friend of Mrs. Lock’s, attended these presentations. He and the Ṭhākura maintained a close relationship. They had extensive discussions on theology, and he mentored the Ṭhākura in his reading of the Bible and other Christian books. The Ṭhākura confesses that he thus developed a deep faith in Jesus Christ.

At some point in 1857, Kedarnath Dutt travelled to Burdwan and presented a copy of his first volume of The Poriade to the King of Burdwan, Maharaja Mahatab Chand, who read some of it and liked it. Upon his return to Calcutta, Kedarnath discovered his grandmother bedridden, on the verge of death. He had been on a high, thinking he would study, write, print books, lecture, and make money, whereby he could find a place for his mother, grandmother, and young wife to all live together finally. But the reality was harsh: his grandmother was dying, there was little money, and he had few trusty acquaintances.

Some time after his grandmother’s death, Kedarnath managed to secure two private tutorships and, after a few months, a position as a second-grade teacher at his former school. Things were looking up. He rented a house in a nice neighborhood called Sunri and furnished it with a couple of canopy beds, a cot, one table, two chairs, and a single clothes rack. He even hired the help of a servant and maid. This he barely managed on a monthly income of fifteen to twenty rupees a month plus whatever he earned from selling copies of The Poriade.

The Ṭhākura writes that while living at the Sunri house, he would frequently visit the poetess, Mrs. Lock. He describes her as an older woman, perhaps to dismiss any untoward assumptions. He confesses, however, that his poetry pleased her and she showed him much affection. He further describes her a spiritualist who showed him many “spiritual” manifestations. Supposedly, she would invoke spirits to dance on her table. The Ṭhākura validates these experiences somewhat, writing, “She could see the spirits, but I could only hear the sound of their dancing.”

Young Kedarnath Dutt did not manage to stay at his rented house in Sunri for more than a few months. His income was not sufficient, and his mother had to sell some jewelry to cover the back rent. He was forced to move his mother and wife to the home of the relative who had accommodated his grandmother. He struggled to find work in Calcutta and, eventually, the next year, in 1858, set out for Orissa at the behest of his paternal grandfather, who had foreseen his own death and wanted the Ṭhākura to be present in Orissa when that occurred.

In Orissa, the Ṭhākura’s fortunes took a turn for the better. There, he managed to have an English school established and gained employment there as a teacher by the personal recommendation of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar. The Poriade still came somewhat in handy there when he entertained English officials who visited. Beyond this, there is no more mention of The Poriade in the Ṭhākura’s autobiography.

The Poriade: An Act of Artful, Devotional Defiance

The task that beckons now is to peruse The Poriade itself for clues as to what heart-stirring truths the Ṭhākura distilled into it that earned the appreciation of the highly artistic and devoted Christian, Mrs. Lock.

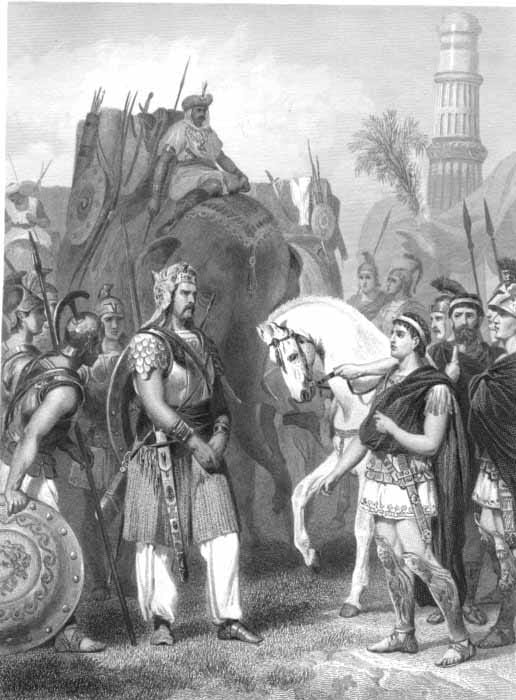

For one, the Ṭhākura’s choice of protagonist—“Pooroo” or Porus, the Indian king of the ancient Vedic clan of Puru who is said to have been defeated by Alexander, even though Alexander then turned back and did not venture any further into India—and the opening lines of his composition express a nationalist fervor that makes clear his feelings as a young Indian man growing up under the looming spectre of the British Raj. But on closer inspection, the Ṭhākura’s composition proves to be more than that. It is a calculated, well-camouflaged move to establish and extol the glories of Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

In the front matter of his booklet, the Ṭhākura adds an “Advertisement” wherein he argues the merits of the poetic vs. the factual, contrasting Shakespeare with Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism. He concludes by asserting that he does not intend to simply “please men at their leisure hours” but also see some historical importance attached to his work.

By his own admission, the Ṭhākura was never much good at math. He was of a more artful bent. As he sat in his maternal grandfather’s home, in the corridor near the deity of Krishna Chandra Ray, studying maths and other subjects he was not so much interested in, what do you, dear reader, suppose crossed his young, fervent mind if not wonder as to the identity and story of Kṛṣṇa? He makes it clear that he always had a longing to know the truth about God. All along he was trying to find Kṛṣṇa, much like Parīkṣit Mahārāja, inquiring from anyone he could on the topic.

Porus was a descendant of Mahārāja Puru and the even more ancient Pururavas, both prominent members of the Candra-vaṁśa, or lunar dynasty, to which both Kṛṣṇa and the Pāṇḍavas belonged. The Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus mentions that Porus’ soldiers bore flags with the insignia of “Herakles,” who is often equated with “Hari Kṛṣṇa.” Ishwari Prasad and other scholars have a string of arguments to fortify the idea that Porus was a Śūrasenī descendent of Kṛṣṇa and the Yadus.

Back in Krishnanagar (“Krishna’s town”), at the very beginning of his educational journey, the Ṭhākura had sat in a stairwell—beneath a figurine of Gaṇeśa by some fateful synchronicity—listening to recitations of the Mahābhārata. He mentions his natural attraction to the character of Bhīma, valiant warrior and dear friend of Kṛṣṇa. The bulky footnotes on the first few pages of The Poriade explaining who Bhīma and Bhīṣma are confirm the Ṭhākura’s enduring appreciation of the Mahābhārata and spell out the Ṭhākura’s designs to weave stories of Bhīma specifically into his poem about Porus, which he intended to consist of twelve parts.

The Ṭhākura’s choice of protagonist was undoubtedly shrewd. The young Kedarnath Dutt knew that he could not debate the English on the historicity of Puranic figures like Kṛṣṇa and the Pāṇḍavas. Meanwhile, the whole of India was in a desperate struggle to resist the British enterprise. The year he published The Poriade was the year of the Sepoy Mutiny, or Indian Rebellion of 1857, one of most significant uprisings against the British East India Company. This work of poetry was the Ṭhakura’s sublimated fight against the British, an appeal to their higher selves and finer sensibilities. It was “the gentle voice of the Muse” he hoped would reach them when they were receptive to it, in their leisure hours.

In countering the British assault on his homeland, the Ṭhākura chose a literary medium and a point of common historical agreement. He made his thinly veiled satirical stand on those grounds, invoking the memory of the previous failed attempt at conquest by a Western power some two thousand years prior. “That didn’t work out too well,” he seems to warn.

Porus, scion of what the Western scholar will perhaps forever view as the mythological lunar dynasty, proved something in his undeniable deterrence of Alexander. His historically acceptable existence is a glorification of Śrī Kṛṣṇa in itself; it speaks not only to the indomitable spirit of Indians in his time or in the Ṭhākura’s time or now, in our time—when India is the most populous nation on Earth and the majority of its citizens cherish Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa in one way or another—but to all children of God resisting the onslaught of exploitation now and forever into the distant past and future. The Ṭhākura’s well-chosen protagonist transcends time and space in his representation of Śrī Kṛṣṇa, for that is the simple effect of one who, like the Ṭhākura and the valiant King Puru, who was presumably a devotee of Kṛṣṇa as well, give their lives in service to that one, ultimate, beautiful reality. Kṛṣṇa defends and empowers those who surrender unto Him, as promised in the Bhagavad Gita.

Woven into the fabric of The Poriade are other eternal truths resonating irrepressibly from the Ṭhākura’s divine heart, like his faith in the holy name as expressed when he writes:

And priests employed, to God, their prayers now

“Almighty Sire, our feeble prayers oh hear!

Thy holy name destroys the gloom of fear;

How oft we asked thy aid, and not in vain!

How oft thy name dispelled our sorrow’s train!

Thy might has wrought this world, thou dost protect;

Thy lash of ruin its vices shall correct;

—The Poriade, pages 10–11

Leisure Hours

The Ṭhākura mentions the title of Mrs. Lock’s collection, Leisure Hours, in his dedication to her, and he uses the same phrase in his “Advertisement” on the following page. It is hard to imagine this was an accident. Was it a deliberate homage to Mrs. Lock? Perhaps. At very least, the two of them should have shared a chuckle or two about it.

The resonance the Ṭhākura and Mrs. Lock shared was undoubtedly a spiritual one, as corroborated by the comments he makes of her in his autobiography and the God-centric soul-searching he says he was engaged in when their friendship flourished. The final comment he makes of Mrs. Lock might paint her as an eccentric sort, but her own poetry casts her as someone who was uniquely sensitive:

Sweet Spirits, too, with folded wings I’ve seen,

In midnight dreams before the “One Most High,”

The dazzling halo round them, Oh, how faint

In the soft beam of thy resplendent eye.

—“Thine Eye” Leisure Hours, pages 61–62

In one poem, “With Whom and What I Sympathize” (Leisure Hours, pages 210–211), Mrs. Lock proudly declares her partiality for the downtrodden, revealing perhaps too much of a savior’s complex, as would fit her occupation as a missionary. That perhaps brings the purity of her friendship with the Ṭhākura into question. How genuine were her sympathies? How much of it was self-serving?

Setting aside those doubts, one fact is undeniable: Mrs. Lock was a genuine admirer of Kashiprasad Ghosh, the Ṭhākura’s uncle and main mentor. Surely her appreciation for the uncle extended to the astute nephew. Some excerpts of her profuse admiration of Kashiprasad as expressed in “Lines – On Reading the ‘Shair and Other Poems’ by Kaśiprasād Ghosh” are as follows:

The feelings of a tender, noble soul

When crushed by stern adversity ’tis laid,

Thy ready pen, e’er dipp’d in living truth,

Hath faithfully and fully here portrayed.

Thy strains so sweet, so pure, so seraph-like,

Flow gently from the living Fount within;

That fount of quenchless, wild, poetic fire,

Which, burning on, a deathless fame shall win.

More worthy hands than mine will twine the wreath

Of laurel round thy high, majestic brow;

And to thy lofty noble—heaven-born mind

Their spirits with humility will bow.

—Leisure Hours, pages 153–154

Judging from these verses, Kashiprasad Ghosh had a profound impact on Mrs. Lock. He could have been a mentor to her, having published his renowned work over fifteen years prior to hers. The connection between Kashiprasad and Mrs. Lock is a story in itself, one that serves to illuminate the bond between her and young Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, as well as his appreciation for her.

Mrs. Lock makes several references to Radha and Krishna, mostly in connection to a particular estate on what used to be the outskirts of Calcutta called Gupta Brindaban, or Seven Tanks. The land the estate is situated on was owned by one Umanandan “Nandalal” Tagore. His mother, near the end of her life, desired to visit Vrindavan, but in those days, going on pilgrimage to far-off holy sites was a perilous undertaking with no certainty of return. To please his mother in her old age, Nandalal put his heart into building a replica of Vrindavan on his vast and scenic tract of land in the Dum Dum area. He even encircled the vast park with seven excavated kundas, or tanks.

Mrs. Lock’s collection opens with “Sunset at the Seven Tanks” and a description of the “Kristo-choora” (kṛṣṇa-cūḍā) flower. She adds a footnote explaining the significance of this flower:

According to the Hindus the god Krishna or Kristo was accustomed to decorate his head with green leaves and flowers of this tree; from the circumstance of the former bearing some resemblance in shape to a peacock’s feather it has obtained its name. “Krishna” is always represented adorned with a peacock’s feather.

This opening page was likely the young Ṭhākura’s introduction to Mrs. Lock’s work. How heartwarming he must have found it, how humbled he must have felt to see an American Christian woman writing about Krishna on the first page of her book. Was it this revelation that elicited the sentiments of an “obliged and obedient servant” in young Kedarnath?

Mrs. Lock carries on extolling Gupta Brindaban for over four pages, describing its beauty and sacred atmosphere, dubbing it an Eden and paradise of joy. She even adds another footnote, explaining the name and its significance for her readers:

Brindia’s private garden. The real “Goopto-Brindia-Bon” is situated at Kasipur or Benares, and received its name in honor of “Brindia,” who, for her faithfulness to “Radhika,” principal wife of the god Kristo, (he had 1600 say the Hindus) obtained her confidence and affection.

Part way through her collection, she glorifies Gupta Brindaban again:

Among the Elysian spots I’ve seen

In these far-distant lands,

The loveliest, and the most renowned

This fairy-garden stands

At the end of her book, in the prose section, she again praises Gupta Brindaban, breaking back into verse form:

Elysian spot! I soon may be called to leave the soil that embraces thee;—

But worthier ones of other name

Will sing thy praise, and speak thy fame:

Sweet nourisson des muses! ’tis meet

You lay your tribute at the feet

Of them who o’er these grounds preside,

Great “Krishna,” and his sacred bride.

From north to south, from east to west,

To Gupta-Brindiabon, the blest!

Bring laurels fresh, and lay them down,

And for each deity form a crown.

The Brilliant and Rasika Kashiprasad Ghosh

It is likely that Kashiprasad Ghosh is responsible for Mrs. Lock’s knowledge of Kṛṣṇa and her enchantment with Gupta Brindaban. In his autobiography, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura mentions several times that Kashi Babu (Kashiprasad Ghosh) lived “in the gardens.” The Ṭhākura does not mention Seven Tanks or Gupta Brindaban, but says that he would visit Kashi Babu and then walk from Paikpara, which is an eight-minute walk from the entrance of the Seven Tanks Estate today, to his college at Patal Danga.

The Ṭhākura also recalls celebrating Sarasvatī Pūjā and Jhulana Yātrā at the house of Kashiprasad Ghosh, which brings us to the topic of Kashiprasad’s own poetry. In 1830, eight years before the Ṭhākura’s birth, Kashiprasad, a youth of twenty-one, was, by his own humble claim, the first Hindu to publish a volume of English poetry. His book, The Shair and Other Poems, drew profuse praise from Anglo-Indian society. He is quoted as saying that though he composed many songs in Bengali, he had a greater body of work in English and found it easier to express himself in English.

The title poem of his collection, “The Shair,” is a lengthy and beautifully crafted creation modelled to some degree on Sir Walter Scott’s The Lay of the Last Minstrel. The next item in Ghosh’s collection is “The Hero’s Reward,” a dramatic, poetic telling of the story of King Pururavā, who became the consort of the most beautiful apsarā, Urvaśī, and is also credited with bringing fire to mankind, which makes him the Vedic Prometheus. Interestingly enough, this Pururavā is the first Puru, ancient forefather of Porus. It might be safe to say Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura found the inspiration for The Poriade in his uncle’s poetry.

One can only wonder what kinds of conversations Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura must have had with his literary genuis of an uncle who had recognized his potential, brought him to Calcutta, and aided him at every step of his development. Kashiprasad Ghosh undoubtedly played a profound role in what were very formative years for the Ṭhākura, and it is possible he sowed the seed of something most sacred and esoteric: vraja-bhakti, and more specifically, madhura-rasa-upāsanā.

Why this claim? Well, the central portion of Ghosh’s collection features eleven poems, each dealing with a different Hindu festival ranging from Daśaharā to Akṣayā Tritiyā. The following are excerpts from poems discussing Rāsa-yātrā, Janmāṣṭamī, and Jhūlana-yātrā:

(Rāsa Yātrā)

IV

Behold young Krishna’s azure hue

Is like the spring-cloud’s lovely blue

With sparkling eyes like diamonds proud.

And there is Rādha by his side,

In budding youth and beauty’s pride,

Like lightning clinging to a cloud.

V

Like the bow that Kāma strings,

Are her lips of ruby light;

Whence the smiles that round she flings,

Like his darts of swiftest flight,

Pierce the youthful bosom deep,

Not, as feigned, with poison’s pain,

But a softness, by which sleep

Griefs and cares—mischance’s train.

(Janmāṣṭamī)

Look, look how beautiful! The new-born boy

Reclines upon its mother’s cautious-arm,

Like young Hope resting in the breast of Joy,

Around whom wantons every infant charm,

Which makes with future hope all bosoms warm

Of thronging men and many a saintly sage,

Who gaze delighted on young Krishna’s form,

For now the long oppressive, baneful age

Will be no more ere long, and fiends will cease to rage.

(Jhūlana Yātrā)

The verdant boughs in Krishna’s bowers,

Of pines and limes are waving gay,

Where pleasures with their hand-maid hours

And rosy love together play

And Krishna there is circled round

With many a youthful maiden fair,

Whose moonbeam-coloured brows are bound

With wreaths of flowers, best growing there.

I leave it to the reader to decide from these excerpts what caliber of devotee Kashiprasad Ghosh may have been. I have my own impression of who he is in relation to Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura and the eternal scheme of Bhagavān’s pastimes, but I cannot declare such a thing openly. Read his poems and decide for yourself.

What remains now is to circle back to Mrs. Lock. There is plenty more to say of her poetry and what it reveals about her, but I will try to be brief and summarize what I have gleaned from my reading.

Mrs. Lock appears to have been a unique personality, especially for her time, who was first drawn to embark on a solo journey to India on the invitation of a “worshipper of Jagannath” who wanted her to educate his young daughter. Her poems, which are often dated, span a number of years and reveal that though she initially had some typically Christian views of bringing enlightenment to Hindu lands, once she lived in India for some time, she fell deeply in love with its atmosphere and people.

She appears to have become disillusioned with the church and those who but wear Christian garb. She glorifies the humble Hindu who is simple and pure at heart while condemning the insincere Christian. At the same time, she stays true to her Christian American values, beckoning Indians to shake off any “morbid religion,” embrace the age of science, and champion the rights of women.

In many places, her poems offer the same kind of wisdom taught in the Vaiṣṇava scriptures. She encourages the Afghan military general Hyder Khan to face to the foes within, “a band more numerous…more powerful—more difficult to subjugate.” She writes incessantly of God, of the beauty and glory of His Creation, of the importance of trusting in Him through times of hardship, and of the importance of tolerance.

Mrs. Lock was clearly someone who felt deeply and also had the ability to express such things effectively. She writes many poems about acquaintances or friends who have passed, manifesting her appreciation of them. She writes of charming young Indian children she met and adored, from which her longing to be a mother is touchingly evident. She writes poems addressed to a sister and nephew back in America whom she misses dearly. She also writes of Jesus with profound devotion, verging on a respectfully romantic love:

I wish on Jesus’ loving breast

To lean my head,—for there is rest;

Rest for the weary, sick and faint,

Peace that will banish all complaint

—“Evening Aspirations” Leisure Hours, page 213

Mrs. Lock clearly possessed qualities befitting any devotee of God and it is safe to say Kashiprasad Ghosh shared his own faith with her, which had a profound and lasting impact. She does not write in glorification of any other poet in her collection. She names him and his collection and gushes over it. Her compositions and footnotes suggest quite plainly that she read, with deep appreciation, Ghosh’s poems of Radha and Krishna and the extensive accompanying endnotes he provided to edify his Western readership.

Mrs. Lock and Mr. Ghosh were about the same age and Ghosh’s fame would have been well established by the time she came into his orbit. If Ghosh did live in the Gupta Brindaban area of Dum Dum, as Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s autobiography suggests, it is possible he was responsible for her distinct appreciation of that garden. Perhaps they had taken strolls there during which he had introduced her to the glories and mysteries of the original Vrindavan. Mrs. Lock shows rather well-informed appreciation for Radha and Krishna in Vrindavan, especially for a missionary Christian. She writes of the Gupta Brindaban garden as her dearest sanctuary, a place of divine inspiration that she expects to miss painfully when she must leave.

Of course, whatever her poetry expresses, Mrs. Lock was perhaps a somewhat different person when she returned to Calcutta almost a decade later, after having been remarried and become a mother. Records of the American Baptist Missionary Union show that she joined her husband the reverend in Prome, Burma, until 1874, when she had to return to America for the sake of her own health. The reverend stayed on and died two years later. “Since that time,” reads Mrs. Lock’s 1899 obituary, “she has resided chiefly in Brooklyn with her sister, and in the midst of many sorrows her trust in the Lord has continued bright and firm, and she has always manifested a lively interest in the missionary work in Burma.”

While it is unclear why Mrs. Lock was back in Calcutta around 1856-’57, it is clear she had maintained her acquaintance with Kashiprasad Ghosh and his circle. The suggestion the Ṭhākura gives in his autobiography is that it was Mrs. Lock who initiated their first meeting through Reverend Dal. Had the Ṭhākura’s uncle prompted this, recommended it? Or had Mrs. Lock taken an interest in the rising young poet Kedarnath of her own accord?

Many questions remain, but an intriguingly opaque image of that period, those personalities, and their connections to each other has emerged. What glows brightest of all is the pure devotion they shared, the evidence of which they each left in black and white, in old booklets of poetry now forgotten by our modern world in its frenzied pace toward the gnashing jaws of greed and destruction. I pray for a return of the gentle, Godly poets of all true religions—if not in person, then in spirit. Might they come to dance on our tables? If we cannot see them, perhaps we might at least hear them.

Sources:

- Dasa, Shukavak N. (1999), Hindu Encounter with Modernity: Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda, Vaiṣṇava Theologian English translation of Svalikhita Jīvanī by Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, (revised, illustrated ed.), Los Angeles, CA: Sanskrit Religions Institute, Svalikhita Jīvanī on Archive.org Retrieved February 18, 2026

- Ghosh, Kashiprasad. The Shair and Other Poems. India Gazette Press, 1830. The Shair and Other Poems (PDF) Retrieved February 20, 2026

- E.L. (L.L. Simons). Leisure Hours: or Desultory Pieces in Prose and Verse. Baptist Mission Press, 1846. Leisure Hours on Google Books Retrieved February 20, 2026

- Dutt, Kedar Nauth. The Poriade or Adventures of Porus, Book 1. G.P. Roy & Co, 1857. The Poriade at Bhaktivinoda Institute Retrieved February 20, 2026

- Das, Soumitra. “Going great guns.” Telegraph India 9 May 2010 Telegraph India Article

- The Baptist Missionary Magazine, Volume LXXIX, published by the American Baptist Missionary Union, Boston, Missionary Rooms, 1899 Baptist Missionary Magazine on Archive.org Retrieved February 18, 2026

- Davis, Hon. Win. J., An Illustrated History of Sacramento County, California. Pages 531-533. Lewis Publishing Company. 1890. © 2005 Karen Pratt. Sacramento County History at Golden Nugget Library Retrieved February 18, 2026

- Bryant, Edwin Francis. Krishna: a Sourcebook, p. 5, Oxford University Press US, 2007 Porus via Wikipedia Retrieved February 20, 2026

- A Comprehensive History of India: The Mauryas & Satavahanas, p. 383, edited by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri, Bharatiya Itihas Parishad, published by Orient Longmans, 1992, Original from the University of California. Porus via Wikipedia Retrieved February 20, 2026